At this festive time of year, it’s become tradition in these parts to publish my Quintessential Guide to Champagne. For those of you who have read it before, feel feel to use it as a refresher and for those new readers, who perhaps didn’t follow along when I used to post about wine, welcome to the world of bubbly!

Thank you to Terry Rogers of Horseneck Wines in Greenwich, my former compatriot in Wednesday Wines, for the incredibly informative and insightful take on the history and making of our favorite holiday drink! What better way to enjoy the holidays than to share a glass of the good stuff with friends and family.

As you may know, in order to be called Champagne the product must be produced within the boundaries of the Champagne Region in France. This Region was delineated many generations ago and must be adhered to with strict regulations. Therefore, when you look at the prices of Champagne and wonder why they are so high, you must realize all the many factors that go into the making of that final bottle. (from Q – At the end of the history and making of champagne, we have some choice suggestions for you).

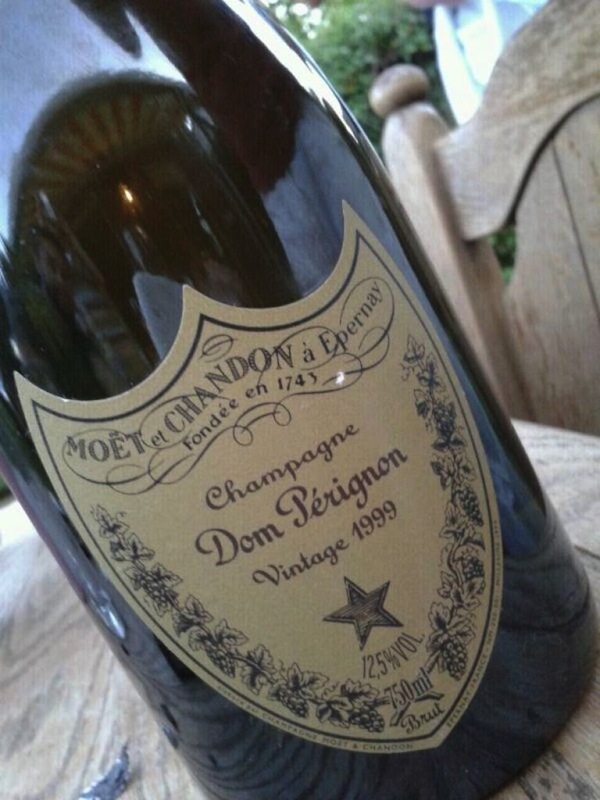

Champagne was developed in France about 300 years ago from a process involving lots of chemistry and many tedious physical manipulations. The history of Champagne dates to about 1700 AD and a monk cellarmaster at the Abbey of Hautvillers near the city of Reims, the “capital” of the Champagne region. As the story goes, a monk named Dom Pérignon was making wine for his colleagues when, unbeknownst to him, he failed to complete the fermentation before bottling and corking the wine. During the cold winter months the fermentation remained dormant, but when spring arrived the contents of the sealed bottles began to warm and fermentation resumed producing carbon dioxide that was trapped in the bottle. Later that spring Dom noticed that bottles of wine in the cellar were exploding, so he opened one that was intact and drank, declaring “Come quickly! I’m drinking stars!” Thus, Champagne was born and named after the region where it was discovered.

Champagne was developed in France about 300 years ago from a process involving lots of chemistry and many tedious physical manipulations. The history of Champagne dates to about 1700 AD and a monk cellarmaster at the Abbey of Hautvillers near the city of Reims, the “capital” of the Champagne region. As the story goes, a monk named Dom Pérignon was making wine for his colleagues when, unbeknownst to him, he failed to complete the fermentation before bottling and corking the wine. During the cold winter months the fermentation remained dormant, but when spring arrived the contents of the sealed bottles began to warm and fermentation resumed producing carbon dioxide that was trapped in the bottle. Later that spring Dom noticed that bottles of wine in the cellar were exploding, so he opened one that was intact and drank, declaring “Come quickly! I’m drinking stars!” Thus, Champagne was born and named after the region where it was discovered.

The key reaction of winemaking is alcoholic fermentation, the conversion of sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide by yeast. The key process in producing Champagne is a SECOND fermentation that occurs in a sealed bottle. The entire process is described below.

The key reaction of winemaking is alcoholic fermentation, the conversion of sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide by yeast. The key process in producing Champagne is a SECOND fermentation that occurs in a sealed bottle. The entire process is described below.

SELECTING THE CUVÉE (La Cuvée)

The cuvée is the base wine selected to make the Champagne. The most expensive Champagnes are made from cuvées from selected vineyards in the Champagne region. Cuvées can be from a pure grape variety, such as Chardonnay or Pinot Noir, or can be a mixture of several grape varieties. Chardonnay is a white grape variety with white juice, Pinot Noir a red grape variety with WHITE juice. Pinot Meunier, a relative of Pinot Noir, also is used extensively. The slight rust color imparted to some Champagne results from using Pinot Noir cuvées that acquire some red color from contact with the skins. The longer the juice remains in contact with the skins, the darker red it becomes. If a Champagne is made exclusively from Chardonnay, it is called “blanc de blanc,” white wine from white grapes. Most Champagne is made from mixed cuvees.

THE TIRAGE

After the cuvée is selected, sugar, yeast, and yeast nutrients are added and the entire concoction, called the tirage, is put in a thick walled glass bottle and sealed with a bottle cap. The tirage is placed in a cool cellar (55-60°F), and allowed to slowly ferment, producing alcohol and carbon dioxide. Since the bottle is sealed, the carbon dioxide cannot escape, and,thereby producing the sparkle of Champagne.

AGING ON DEAD YEAST

As the fermentation proceeds, yeast cells die and after several months, the fermentation is complete. However, the Champagne continues to age in the cool cellar for several more years resulting in a toasty, yeasty characteristic. During this aging period, the yeast cells split open and literally spill their guts into the solution imparting complex, yeasty flavors to the Champagne. The best and most expensive Champagne is aged for five or more years.

RIDDLING (Le Remuage)

After the aging process is complete, the dead yeast cells are removed through a process known as riddling. The Champagne bottle is placed upside down in a holder at a 75° angle. Each day the riddler comes through the cellar and turns the bottle 1/8th of a turn while keeping it upside down. This procedure forces the dead yeast cells into the neck of the bottle where they are subsequently removed. A riddler typically handles 20,000 to 30,000 bottles per day.

DISGORGING

The Champagne bottle is kept upside down while the neck is frozen in an ice-salt bath. This procedure results in the formation of a plug of frozen wine containing the dead yeast cells. The bottle cap is then removed and the pressure of the carbon dioxide gas in the bottle forces the plug of frozen wine out leaving behind clear Champagne. At this point the DOSAGE, a mixture of white wine, brandy, and sugar, is added to adjust the sweetness level of the wine and to top up the bottle. The bottle is then corked and the cork wired down to secure the high internal pressure of the carbon dioxide.The sweetness levels of Champagne range very dry (ultra brut) to very sweet (doux), with brut being the most common.

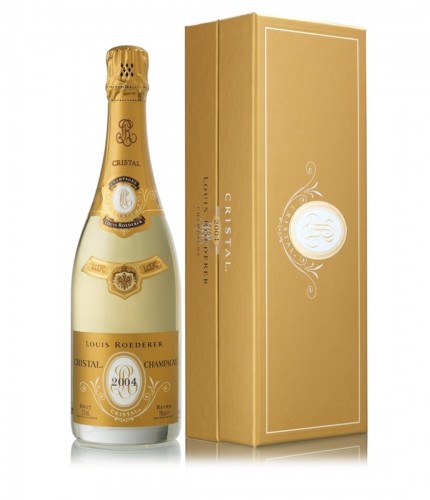

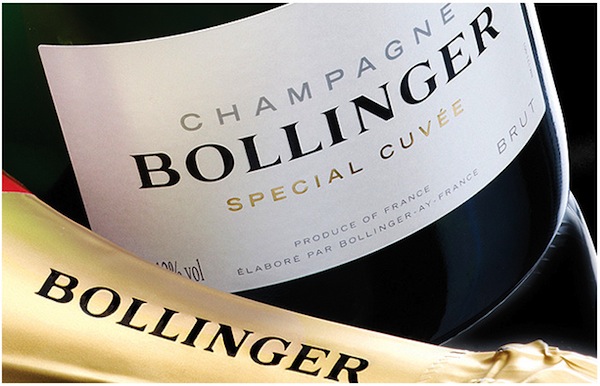

Many Champagne houses produce ”luxury cuvées,” their best and most expensive wines. Dom Pérignon is the luxury cuvée of Möet & Chandon; Cristal is the pride of Roederer. Bollinger produces R.D. or “recently disgorged” wines. For example, you can purchase a 1982 Bollinger R.D. that was disgorged in April 1991, nine years after being placed in the bottle. (from Q – we served an vintage RD at our wedding).

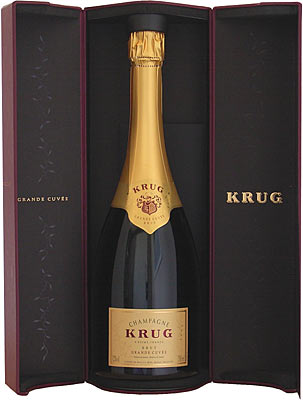

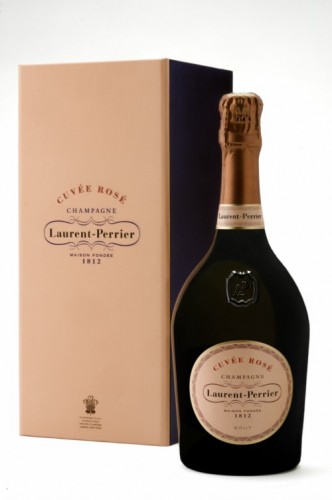

Terry travels to Champagne almost every fall to see the harvest and renew her spirit with “the greatest beverage known to mankind.” Please visit my Champagne 101 post if you would like to take a vicarious trip to four of her favorite Champagne houses: Krug, Billecart-Salmon, Laurent Perrier and Salon.

Terry travels to Champagne almost every fall to see the harvest and renew her spirit with “the greatest beverage known to mankind.” Please visit my Champagne 101 post if you would like to take a vicarious trip to four of her favorite Champagne houses: Krug, Billecart-Salmon, Laurent Perrier and Salon.

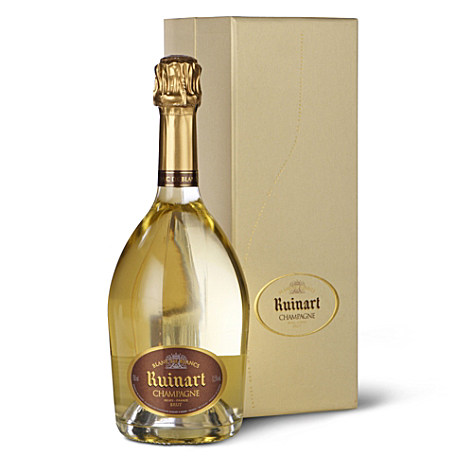

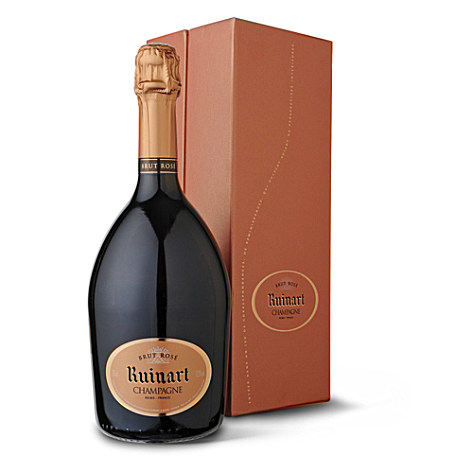

For those looking for some suggestions, here are a few of Terry’s classic picks.

Ruinart blanc de blancs (non vintage), the flagship of their house

Ruinart Rosé (non vintage)

Laurent-Perrier Brut non vintage

Laurent-Perrier Brut non vintage

Laurent Perrier Rosé

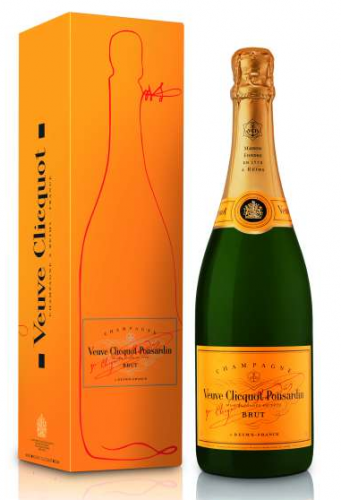

Veuve Clicquote brut non vintage

Veuve Clicquot La Grand Dame 1998

Louis Roederer brut premier non vintage

Louis Roederer Cristal 2004

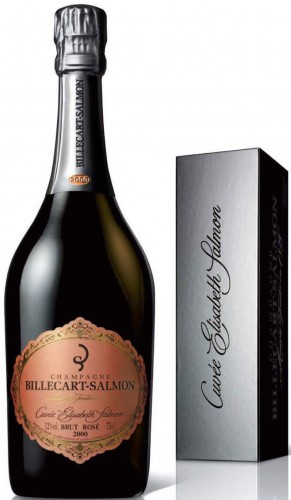

Billecart-Salmon Brut Rosé (non vintage)

Billecart-Salmon Brut Rosé (non vintage)

Billecart-Salmon Cuvée Elisabeth Salmon Rose 1999

Billecart-Salmon Cuvée Elisabeth Salmon Rose 1999

Dom Perignon 2002

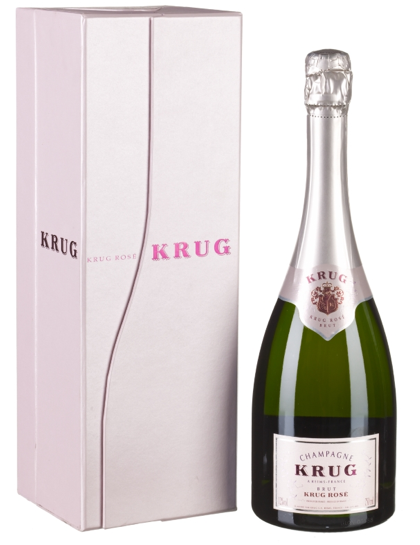

Krug Grand Cuvee is a blend of their various vintages and is always a stellar Champagne for the price. The Krug wines commonly display a subtle nuttiness. Krug uses complete barrel fermentation which is not so common in most of the champagne houses.

Krug Grand Cuvee is a blend of their various vintages and is always a stellar Champagne for the price. The Krug wines commonly display a subtle nuttiness. Krug uses complete barrel fermentation which is not so common in most of the champagne houses.

Krug Rosé Brut NV

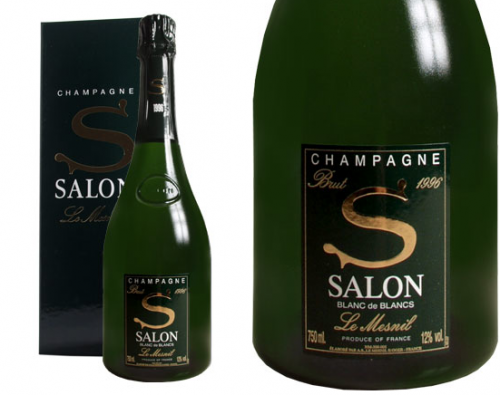

Salon Blanc de Blanc Brut Les Mesnil 1999

These of course do not include the ever expanding list of grower champagnes that are wines produced exclusively from the owners’ vineyards (as opposed to the larger houses who cull grapes from many sources). Last month, Jay McInerney wrote about two of the mid-sized (larger than grower), still-family-owned champagne houses in the WSJ. Bollinger, a personal favorite, is what I will be serving tomorrow night. For those of you who like a fuller flavor, the toasty richness is one I can recommend.

But before you indulge as we enter a new year, be sure to stop back here tomorrow for a special year end video treat!

But before you indulge as we enter a new year, be sure to stop back here tomorrow for a special year end video treat!

I love the Champagne Region of France. Reims is a wonderful and lovely city. The magnificent cathedral with windows by Marc Chagall. But my favorite champagnes come from Epernay. I am an I planning. Trip to Champagne this fall.

I’ll have what she’s having in the second photo! franki

love Reims, was there briefly, great informative post…..cheers to 2014 Debra