Giant of photography that is. As if there weren’t enough reasons to go to Paris already, there is now another. The Jeu de Paume Museum is showing the first major European retrospective of Andre Kertesz, one of my all time favorite photographers.

Born in Hungary in 1894, Kertesz started to explore with a camera when he was 16, while working as a clerk at the Budapest stock exchange. Inspired by life itself, Kertesz used his camera as a sketchbook, recording the majesty of everyday scenes. He explained, “I photographed real life—not the way it was, but the way I felt it. This is the most important thing: not analyzing, but feeling.”

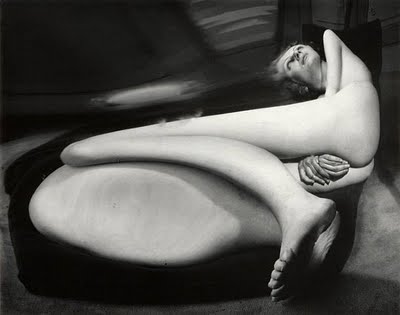

Underwater Swimmer from 1917, below, became a precursor for Kertesz’s later fascination with the distortion of the body that permeated much of his work in the early 1930’s.

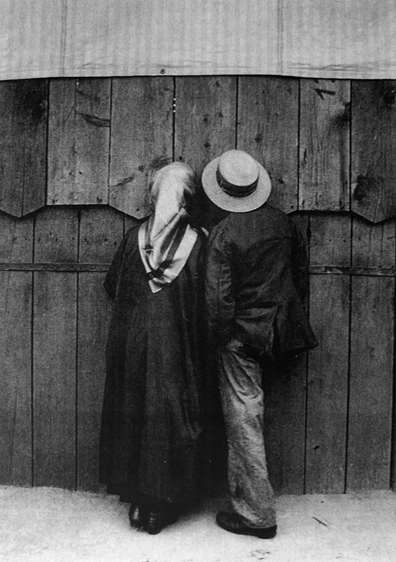

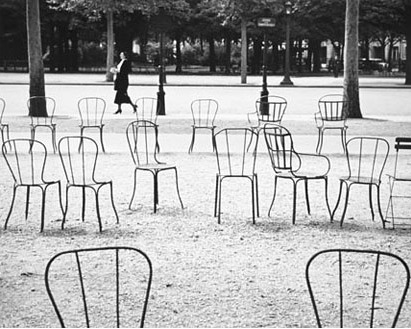

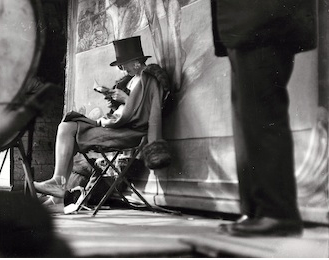

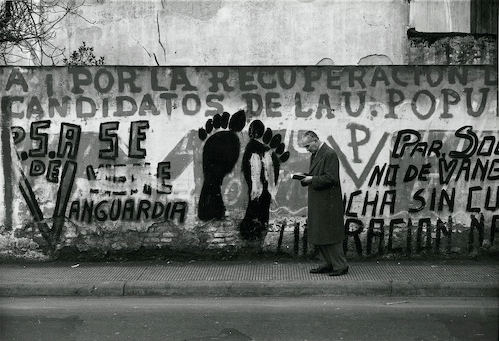

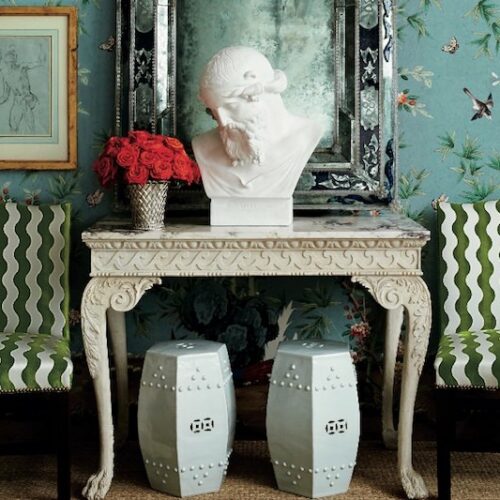

After years of photographing as a hobby in Hungary, Kertesz finally moved to Paris in 1925 where he officially began his career as a photographer. He would wander the streets, capturing intimate scenes that infused his work with its distinctive character. A master of shade and light, he also had a natural eye for form and composition.

During this time in Paris, he met and photographed other artists including Mondrian, Marc Chagall, the writer Colette, and film-maker Sergei Eisenstein and became the first photographer to have a one man exhibition. He served as a mentor to other photographers who went on to have illustrious careers of their own such as Brassai and Henri Cartier-Bresson, who said, “Whatever we have done, Kertesz did first”.

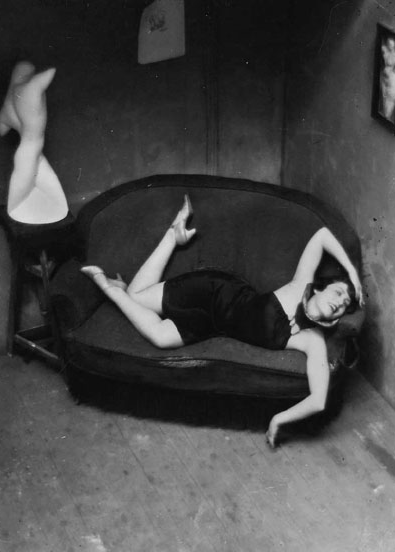

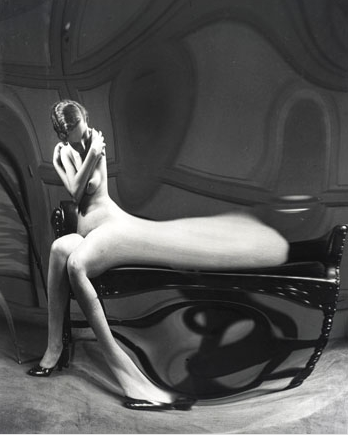

In the 1920’s and 30’s, Paris was a center of intense avant-garde creative activity, attracting artists from all over the world. Kertesz’ Satiric Dancer from 1926, below, shows his interest in the dreamlike vision of Surrealism, a concept popular at the time, that also attracted other photographers such as Man Ray, Brassai, and Ilse Bing.

In 1933, he was asked to contribute some nude photographs to the Parisian magazine Le Sourire (The Smile). This is when his interest in the visual distortions of the body reemerged. Using mirrors and special lenses, Kertesz was able to create these artistic visions. Very Dali-like, no?

Feeling the mounting pressure of pre-WWII Europe, Kertesz moved to New York in 1936. But things did not work out professionally the way he had hoped. A catalogue for one of his shows explained that Kertesz identified with the little cloud in this shot because “it didn’t know which way to go”.

Kertesz was frustrated in New York. He worked for the many illustrated magazines, from Harper’s Bazaar and Town and Country to Life and Look and House and Garden. But he felt his personal work was suffering and was ultimately slighted when not included in Steichen‘s famous The Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955.

But the 1960s saw a resurgence in his popularity and the new photography director of the MoMA, John Szarkowski, featured him in a solo show in 1964. By the 1970’s Kertesz was exhibiting regularly and enjoyed world wide acclaim.

In 1983, Kertesz was featured in the Master Photographers, a program that the BBC produced. This is the first episode.

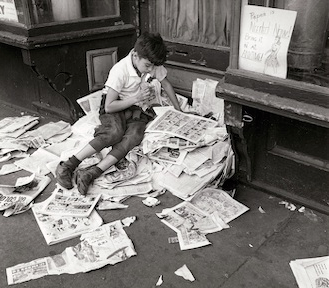

Kertesz published several books during his lifetime, but my favorite is On Reading. Originally published in 1971, it is a charming volume of photographs featuring people – yes, you guessed it, reading. The pictures, taken from 1920 – 1970 focus on people reading everywhere, from Hungary to France to other locales around the globe, in every conceivable situation.

Kertesz continued to work his entire life. In his later years, he received many awards including the Legion of Honor, which the French government awarded him in 1983. He died in New York in 1985.

Such a lovely informative post, Q. My son is a commercial photographer; he studied at Parsons in Paris for 3 years & knows of this gentleman’s iconic work.

He was far ahead of his time, wasn’t he? I mean the distortions of photography into a very contemporary realm of his own. xx’s

splenderosa – Lucky son – 3 years in paris! yes, kertesz was indeed ahead of his time – I think his work will always look modern.

Kertesz is the very first photographer that made me understand many years ago that photography is as much an art form as a painting or a piece of music. The “Stairs at Monmartre” is to me a compositional masterpiece, and it makes me wonder if he spent a lot of time waiting for the shadows and people to be in a position he thought was just right, or he just happened to be there and spotted a perfect opportunity. I wonder if he took many shots and kept the one he liked best, or managed to get just a handful and chose this one.

Harrison – interesting question. I suspect that it was a combination of Kertesz’ excellent eye, timing and circumstance.