Gainsborough at The Frick Collection

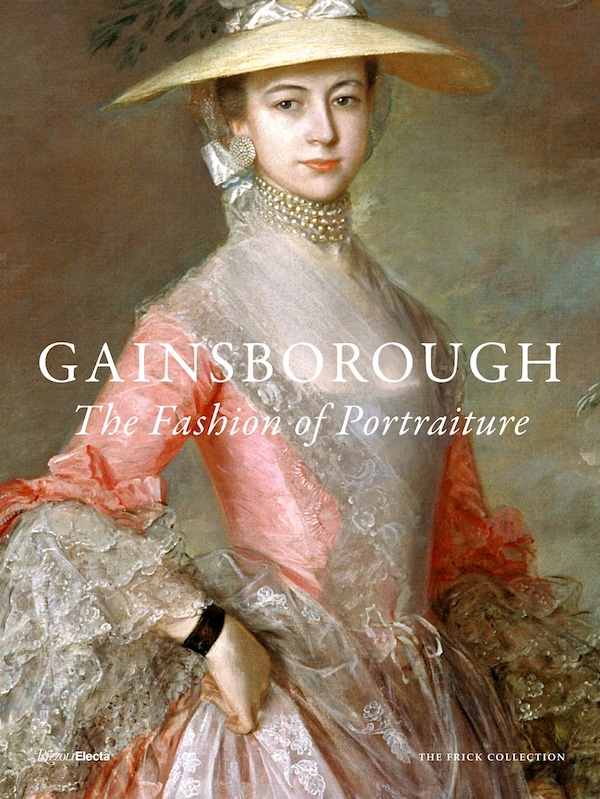

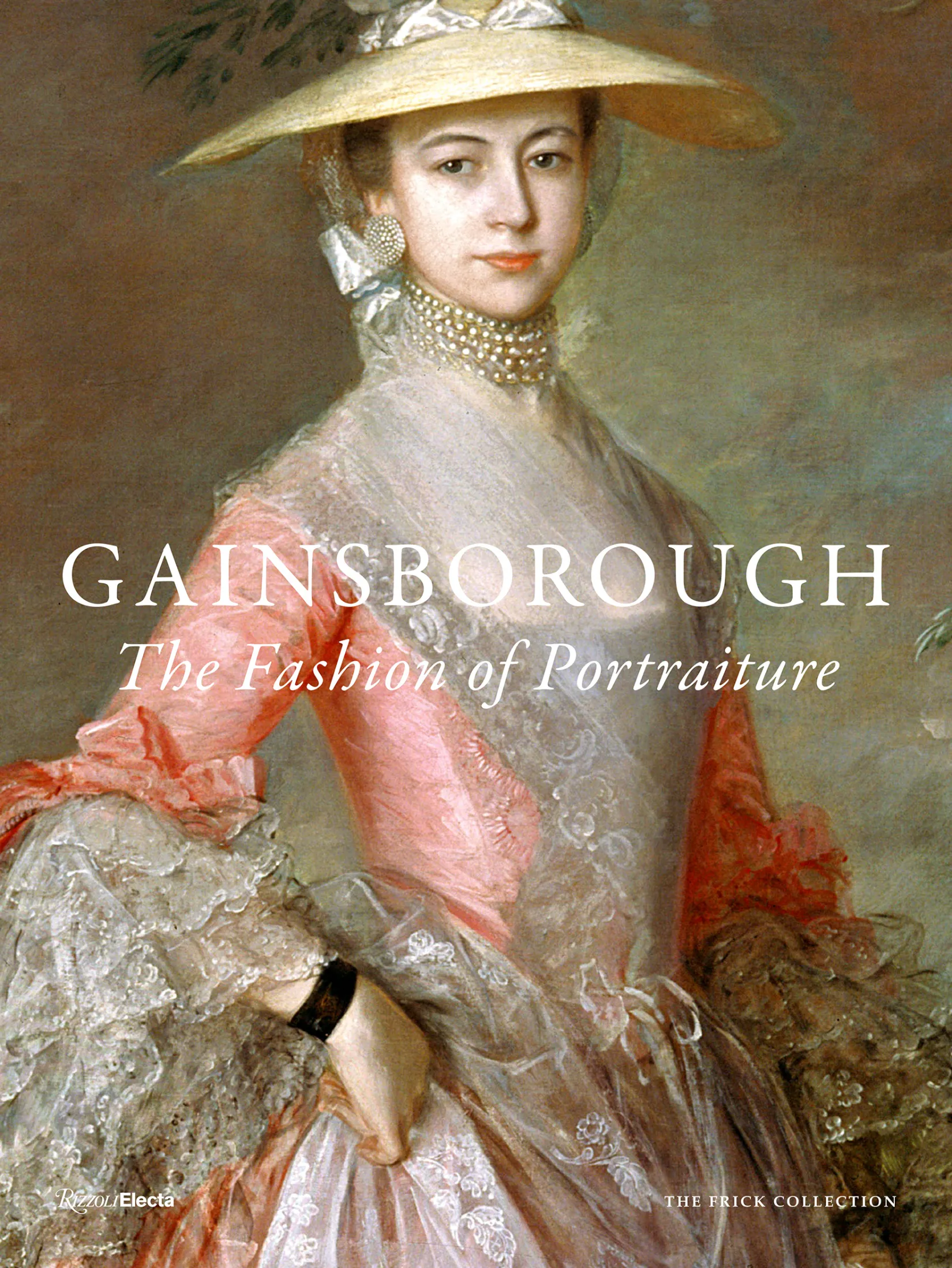

When The Frick Collection opens Gainsborough: The Fashion of Portraiture on Thursday, it will offer New York its first exhibition devoted entirely to the English artist’s portraits—and, in the process, a fresh way of looking not just at eighteenth-century portraits, but at what they reveal about style, status, and self-expression. Gainsborough: The Fashion of Portraiture, on view from February 12 through May 25, 2026, is the first New York exhibition devoted entirely to the English artist’s portraits and the Frick’s first focused presentation of his work.

Bringing together more than two dozen paintings from collections in the United States and the United Kingdom, the exhibition explores how fashion functioned in Gainsborough’s world—not simply as clothing, but as a way of communicating identity. In the eighteenth century, what one wore could signal ambition, profession, intimacy, or social standing. Gainsborough understood this deeply, and his portraits reflect a society keenly aware of how it appeared.

One of the exhibition’s earliest highlights, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, above, shows a young couple posed outdoors, their elegant attire woven seamlessly into a meticulously rendered landscape. Mrs. Andrews’s crisp blue dress and her husband’s tailored shooting jacket do more than signal wealth; they situate the couple within the land they own, merging fashion, property, and identity into a single image.

The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

Gainsborough’s society portraits reveal how clothing could shape reputation. In Sarah Hodges, Later Lady Innes (ca. 1759), the sitter’s carefully chosen attire plays a central role in presenting her as a woman of refinement and promise. Painted before her marriage into the aristocracy, the portrait uses dress, posture, and expression to anticipate social ascent—fashion operating not only as reflection, but as projection.

In his portrait of Grace Dalrymple Elliott, above, Gainsborough had a different challenge. For a woman whose life was marked by scandal rather than noble lineage, the artist turns to the elevated language of “Van Dyck dress.” The deliberately old-fashioned style referencing the seventeenth-century master, lends her an air of dignity and distinction, demonstrating how fashion—and portraiture itself—could be used not simply to reflect social standing, but to reinterpret it.

The exhibition also broadens the picture of who was included in fashionable society. A striking pairing, above, brings together portraits of Mary, Duchess of Montagu, and her servant, Ignatius Sancho. Born into enslavement and later celebrated as a composer, writer, and abolitionist voice, Sancho is depicted not in servant’s livery but in the refined coat and waistcoat of a gentleman. The choice is subtle but powerful, quietly challenging assumptions about race, status, and belonging in Georgian Britain.

Gainsborough’s sensitivity to fashion and status extended even beyond human sitters. In Pomeranian and Puppy, below, a small dog and her offspring are presented with the same care typically reserved for aristocratic subjects. The alert posture, glossy coat, and composed arrangement echo the conventions of elite portraiture, gently underscoring how ideas of refinement, breeding, and display permeated every level of eighteenth-century society—even its pets.

Organized by Aimee Ng, the Frick’s Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, the exhibition pairs visual splendor with reflection, revealing how fashion and portraiture alike were carefully constructed—part truth, part aspiration. A full calendar of public programs will accompany the exhibition, including talks, seminars, concerts and a conversation between Ng and fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi. A 200 page illustrated catalogue authored by Ng, with a contribution by Kari Rayner, Associate Conservator of Paintings, J. Paul Getty Museum will also be available.

At its heart, Gainsborough: The Fashion of Portraiture is about how people wished to be seen—and how images helped make those wishes last. The world may have changed, but the impulse to express identity through appearance remains as familiar as ever.

Gorgeous paintings, and the clothes are just fabulous. I have not been to the Frick in literally decades, mainly because I live on the west coast. Thank you for reminding me that I need to get to NYC more often!

My pleasure – the new Frick is spectacular as is the new restaurant, which I wrote about here https://quintessenceblog.com/q-tips/welcome-westmoreland-the-fricks-new-cafe/